Once you’re aboard your sailing vessel in the Whitsundays, each leg of your trip will require planning as you go. This will be largely governed by two factors: weather and tide. Or, to put it more precisely, wind and current. These two elements govern whether you have a smooth, fast and enjoyable journey, or an uncomfortable or even unsafe one.

Knowing your limits

Every craft and crew will have it’s limits. Getting to know those is a process of trial and error. It is always best to err on the side of the former, gradually increasing your exposure to the elements, rather than jumping in at the deep end. Because when boating, if providence should see it so, the deep end can be very very deep.

For our 2011 research trip, our runabout boat was about 5 metres long, had some protection from the elements in the form of a half-cabin, was capable of good speeds and was pretty solid. But we had our limits – ours was about 15 knots of wind, and knowing if it gusted to 17-19, we’d be OK.

The weather forecast

Knowing what to expect from the wind, in terms of direction and strength throughout the day of our trip is critical because it is this that drives many other factors such as wave height and intensity, or when is best to travel given the tidal state. Whether the weather is fine or whether the weather is wet, is a secondary, unimportant factor.

There are numerous ways to get wind forecast information: through VHF radio broadcasts; going online; looking at noticeboards of seafaring service providers; even the television. However our preferred method is to go online, because it’s the most up to date and depending where you look, you can get very detailed, hour by hour forecast data.

However, while these sources may be detailed, they are not particularly accurate in my experience of late. Nor are any other forms of getting the forecast for the Whitsunday Islands. They are only predictions, and those can be flawed. All use some component of Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) data to make a call. It is probably best to looking at all the forecasts and then work out which elements you choose to believe based on experience and prudence.

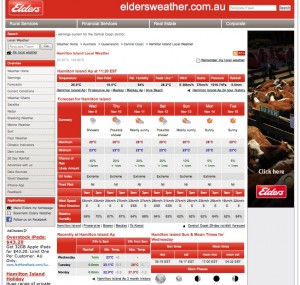

For example, Elders Weather is great for an indication of strength, because it’s always a few knots stronger than the others. One a recent trip we experienced a stubborn southeasterly trade wind that refused to make way for summer and these winds seemed to always blow stronger than predicted. Elders Weather has an iPhone app, and is also specific to Hamilton Island, which is a pretty good indicator of what things will be like out there among the islands.

For example, Elders Weather is great for an indication of strength, because it’s always a few knots stronger than the others. One a recent trip we experienced a stubborn southeasterly trade wind that refused to make way for summer and these winds seemed to always blow stronger than predicted. Elders Weather has an iPhone app, and is also specific to Hamilton Island, which is a pretty good indicator of what things will be like out there among the islands.

To get wind direction, try Windfinder which has some great detailed data on wind strength and direction, wave height and direction and broken down into three hour blocks. It is also specific to Hamilton Island. This site makes a pretty good call on the wind direction, but the strengths are usually too conservative.

To get wind direction, try Windfinder which has some great detailed data on wind strength and direction, wave height and direction and broken down into three hour blocks. It is also specific to Hamilton Island. This site makes a pretty good call on the wind direction, but the strengths are usually too conservative.

Then, there’s Seabreeze which does the best job of visualising the data. Down the coast around Jervis Bay where we live and in Sydney it is awesome for wind direction and wave height, but it isn’t accurate at direction or strength up here in the Whitsundays. It seems to take a pretty wide area from Hamilton Island to Gladstone and try to provide a forecast for what is a rather large swathe of coast. However, it does give a good general hour by hour trend pattern that you can see readily, so you can refer to it to get a sense of what the week might look like at a macro scale.

Then, there’s Seabreeze which does the best job of visualising the data. Down the coast around Jervis Bay where we live and in Sydney it is awesome for wind direction and wave height, but it isn’t accurate at direction or strength up here in the Whitsundays. It seems to take a pretty wide area from Hamilton Island to Gladstone and try to provide a forecast for what is a rather large swathe of coast. However, it does give a good general hour by hour trend pattern that you can see readily, so you can refer to it to get a sense of what the week might look like at a macro scale.

Assessing the tidal situation for current predictions

So, once I have a picture of the likely wind strength at various times of day, I then look at the tides and what they’ll be doing. Right now that is a matter of looking at a tide chart for Shute Harbour and using maths to calculate what it will be like where we’re going, which is a pain. So, I have an iPhone and an app calledWorld Tides which is really good and tells me what it will be like at a slightly more specific location, but it’s not cheap as they go, particularly because I have to re-buy it every year for up-to-date data.

So, once I have a picture of the likely wind strength at various times of day, I then look at the tides and what they’ll be doing. Right now that is a matter of looking at a tide chart for Shute Harbour and using maths to calculate what it will be like where we’re going, which is a pain. So, I have an iPhone and an app calledWorld Tides which is really good and tells me what it will be like at a slightly more specific location, but it’s not cheap as they go, particularly because I have to re-buy it every year for up-to-date data.

Tide is important because it equates to current. Tides in this part of the world are big, and correspondingly, current is strong, particularly around these islands where there are narrows and channels, etc. When the moon is full or new (these are when we get “spring tides”, not just in the season of spring, as the name suggests), the tides a much bigger and currents are correspondingly fiercer. We’re in a powerboat, so up to 5 knots of current slowing us down isn’t a big bother, but if we were in a sailboat, then it could mean a quick or very long trip to our destination.

Aligning current and wind together

But one thing that applies to powerboats and sailboats equally, is sea state and chop and this is made from the combination of wind and current directions. A choppy, confused sea is uncomfortable and can be dangerous, so we like to avoid those as much as possible, especially if we’ll be heading into it (travelling in the opposite direction to the wind and chop, as opposed to travelling with it in the same direction). That means, if the wind is blowing from 8-15 knots from the southeast, then we want the current to be heading that way too. Because, if it’s heading in the opposite direction (northwest) then any stretch of open water between the islands (e.g. The Molle Channel, Whitsunday Passage, etc) is going to be all steep and confused.

In the Whitsundays the current generally moves southward when the tide is flooding (rising) and northward when it’s ebbing (falling). Because the Molle Channel and Whitsunday Passage run vaguely northwest to southeast, a forecast southeasterly wind is going to blow up (northward) those bodies of open water. So, when I look at my wind and current data together, I know I want to be heading out of Shute Harbour on the mainland on an ebbing tide, aligning wind and tide together. This will minimise the amount of bashing the boat does. If we were in a sailboat, we might make a different decision, because the current pushing us along might be worth the discomfort or may in fact make our passage impossible if sailing against it.

Of course, leaving on an ebbing tide has its disadvantages for the camper. Many of our destinations need to be arrived at on a mid to high tide for there to be access over the reef. We can find this information in 100 Magic Miles. So… that means sometimes we have to leave at the very beginning of the ebb tide, so it’s not too far down when we get there. And, when we disembark, we have to be careful that the boat doesn’t get stuck on the beach as the water disappears beneath it. But, this is easier to deal with than a horrible feeling of being half way across Whitsunday Passage with wind against tide, the sea choppy as hell and feeling you might’ve bitten off more than you could chew.